Chapter 54 Speed up in r programming

Hongling Liu and Xinrui Zhang

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

library(microbenchmark)

library(compiler)

library(Rcpp)

library(parallel)It is well known that R is not a fast language, since R was deliberately designed to simplify our process of performing data analysis and statistics, rather than making life easier for our computers to process. While R is slow compared to some other programming languages, it’s fast enough for most of our purposes.

The goal of our community contribution is to give you a deeper understanding of how we could yield the maximum efficiency when running R. We will first introduce the typical development cycle computational statistics with R and what is some of R’s performance characteristics, to help you understand how R codes are being executed. We will also show you two relatively easy ways to speed up code using the Rcpp package and parallel processing.

54.1 Typical development cycle for computational statistics

First, let’s take a look at the usual steps of computational statistics with R, and what questions we need to ask ourselves for each step:

Scientific planning: What experiments would verify/invalidate our hypotheses? What parameter settings should we consider?

Code planning: What does the code need to do? How will the code fit together? What functions will be used? What are their inputs/outputs etc.

Implementation:

Prototype functions, classes, etc., partial documentation

Write unit tests

Implement code, run unit tests, debug

Broader testing, more debugging

Profile code, identify bottlenecks

Optimize code

Conduct experiments.

Full documentation.

54.2 Bytecode compilation

After profiling, what can we do to improve performance?

Questions to ask ourselves: Are there obvious speedups? Are things being computed unnecessarily? Are you using a

data.framewhere you should be using a matrix etc.Look up your problem on internet (e.g., search for “lapply slow” or “speeding up

lapply” etc.)Try the just-in-time (JIT) compiler.

Consider re-writing some or all of the code in a compiled language (e.g., C/C++).

Try parallelization.

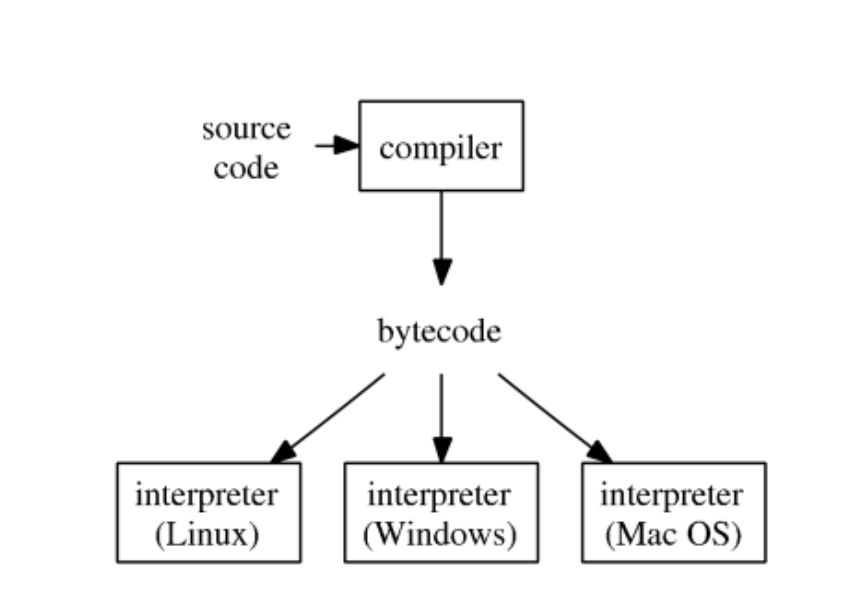

R typical execution:

- Since R 2.1.4, the

compilerpackage by Luke Tierney is distributed with base R.compilerpackage compiles an R function into bytecode.

54.2.1 Example: summing a vector

Brute-force for loop for summing a vector:

sum_r <- function(x) {

sumx <- 0.0

for (i in 1:length(x)) {

sumx <- sumx + x[i]

}

return(sumx)

}

sum_r## function(x) {

## sumx <- 0.0

## for (i in 1:length(x)) {

## sumx <- sumx + x[i]

## }

## return(sumx)

## }Run the code on 1e6 elements:

library(microbenchmark)

library(ggplot2)

x = seq(from = 0, to = 100, by = 0.0001)

microbenchmark(sum_r(x))## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq mean median uq max neval

## sum_r(x) 35.0608 35.1252 35.34773 35.1716 35.2753 40.5348 100Let’s compile the function into bytecode sum_rc and benchmark again:

## function(x) {

## sumx <- 0.0

## for (i in 1:length(x)) {

## sumx <- sumx + x[i]

## }

## return(sumx)

## }

## <bytecode: 0x5584b81f6ef0>Benchmark again:

## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq mean median uq max neval cld

## sum_r(x) 35.0601 35.09905 35.35134 35.14455 35.30405 37.5750 100 a

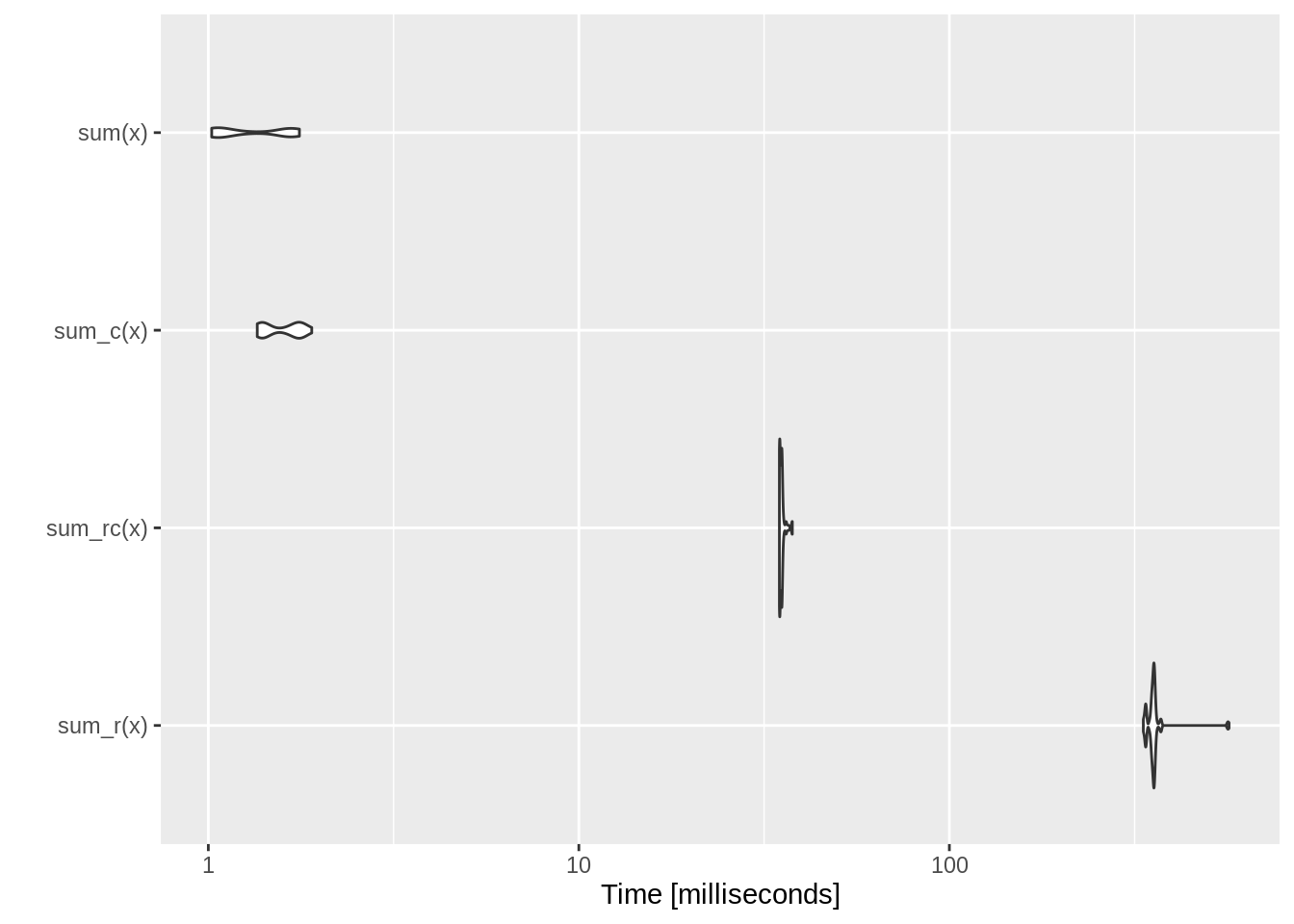

## sum_rc(x) 35.0736 35.10195 35.29535 35.13505 35.21115 37.5022 100 aBefore we look into the results, let’s look at the microbenchmark function. Here we use it as a more accurate replacement of the often seen system.time( ) expression to accurately measure the time it takes to evaluate expr. Since we are only measuring the performance of a very small piece of code, we could get the accurate running time in milliseconds(ms), microseconds (µs) or even nanoseconds (ns) by using microbenchmark.

microbenchmark( ) runs each expression 100 times by default (it can be controlled by the times parameter). In the process, it also randomises the order of the expressions. It summarises the results with a minimum (min), lower quartile (lq), median, upper quartile (uq), and maximum (max). By default, microbenchmark( ) runs each expression 100 times (controlled by the times parameter). In the process, it also randomises the order of the expressions. It summarises the results with a minimum (min), lower quartile (lq), median, upper quartile (uq), and maximum (max). We could focus on the median and mean, and use the upper and lower quartiles (lq and uq) to get a feel for the variability.

In our example, we can see that compiling into bytecode does not make a big difference, since according to microbenchmark(), the running time of our sum_r function is mostly (more than half) in the interquartile range(34.8257,35.02315), and after compiling, the interquartile range for sum_rc(x) is (34.86815,35.1907), so we could say that compiling into bytecode does not help much.

The reason behind this may be seen at the following code where we found out that the function sum_r is already compiled into bytecode before execution.

## function(x) {

## sumx <- 0.0

## for (i in 1:length(x)) {

## sumx <- sumx + x[i]

## }

## return(sumx)

## }

## <bytecode: 0x5584b1999b20>Let’s turn off JIT (just-in-time compilation), re-define the (same) sum_r function, and benchmark again:

## [1] 3sum_r <- function(x) {

sumx <- 0.0

for (i in 1:length(x)) {

sumx <- sumx + x[i]

}

return(sumx)

}

microbenchmark(sum_r(x))## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq mean median uq max neval

## sum_r(x) 348.6904 353.7995 361.0195 355.7976 359.1445 577.1574 100Now we witness the slowness of the un-compiled sum_r.

Documentation of enableJIT:

enableJIT enables or disables just-in-time (JIT) compilation. JIT is disabled if the argument is 0. If level is 1 then larger closures are compiled before their first use. If level is 2, then some small closures are also compiled before their second use. If level is 3 then in addition all top level loops are compiled before they are executed. JIT level 3 requires the compiler option optimize to be 2 or 3. The JIT level can also be selected by starting R with the environment variable R_ENABLE_JIT set to one of these values. Calling enableJIT with a negative argument returns the current JIT level. The default JIT level is 3.

Since R 3.4.0 (Apr 2017), the JIT (‘Just In Time’) bytecode compiler is enabled by default at its level 3.

If you create a package, then you automatically compile the package on installation by adding

to the DESCRIPTION file.

54.3 Rcpp

Now, we are going to introduce the package Rcpp which helps yield the maximum efficiency for R. And there is a learning source for whoever interested:

- Advanced R: https://adv-r.hadley.nz/rcpp.html

We previously used compiler package to compile R code into bytecode, which is translated to machine code by interpreter during execution. However, A low-level language such as C, C++, and Fortran is compiled into machine code directly, making it easy for our computer to process the code, and Rcpp makes it very simple to connect C++ to R, where it allows us to write C++ functions in R, therefore yielding the maximum efficiency.

54.3.1 Use cppFunction

Rcpp package provides a convenient way to embed C++ code in R code.

library(Rcpp)

cppFunction('double sum_c(NumericVector x) {

int n = x.size();

double total = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

total += x[i];

}

return total;

}')

sum_c## function (x)

## .Call(<pointer: 0x7f8a86f6c620>, x)Benchmark (1) compiled C++ function sum_c together with (2) R function sum_r, (3) compiled R function sum_rc, and (4) the sum function in base R:

## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq mean median uq max neval cld

## sum_r(x) 333.8041 351.39795 359.413712 355.35945 357.9218 568.6876 100 c

## sum_rc(x) 34.7744 34.83755 35.239997 35.18255 35.3564 37.6875 100 b

## sum_c(x) 1.3554 1.39690 1.589323 1.62370 1.7625 1.9016 100 a

## sum(x) 1.0213 1.04850 1.341310 1.20020 1.6717 1.7613 100 a

Remember we turned off JIT by enableGIT(0) earlier.

This is a good example of where C++ is much more efficient than R. As shown by the above microbenchmark, sum_c() is competitive with the built-in (and highly optimised) sum(), while sum_r() is several orders of magnitude slower.

Therefore,Rcpp package is definitely a great tool for us to improve the efficiency for our R code.

54.4 Parallel computing

Now, we are going to discuss another way to get efficient with R – parallel computing:

Fact: base R was designed to be single-threaded. Even you request a fancy instance with 96 vCPUs, running R code is just using 1/96th of its power.

To perform multi-core computation in R:

Option 1: Manually run multiple R sessions.

Option 2: Make multiple

system("Rscript")calls. Typically automated by a scripting language (Python, Perl, shell script) or within ROption 3: Use package

parallel.

parallelpackage in R.Authors: Brian Ripley, Luke Tieney, Simon Urbanek.

Included in base R since 2.14.0 (2011).

Based on the

snow(Luke Tierney) andmulticore(Simon Urbanek) packages.To find the number of cores:

## [1] 254.4.1 Simulation example

Senario: Suppose we have a new method to calculate average, that is, to only choose primed-indexed number to calculate the average, and we would like to compute the average mean squared error (MSE) from both this new method and the classic method. Differently distributed random variables with different sample sizes will be tested. There are going to be many combinations of distribution and sample size.

\[ MSE = \frac{\sum_{r=1}^{\text{rep}} (\widehat \mu_r - \mu_{\text{true}})^2}{\text{rep}} \]

## check if a given integer is prime

isPrime = function(n) {

if (n <= 3) {

return (TRUE)

}

if (any((n %% 2:floor(sqrt(n))) == 0)) {

return (FALSE)

}

return (TRUE)

}

## estimate mean only using observation with prime indices

estMeanPrimes = function(x) {

n <- length(x)

ind <- sapply(1:n, isPrime)

return (mean(x[ind]))

}

## compare methods: sample avg and prime-indexed avg

compare_methods <- function(dist = "gaussian", n = 100, reps = 100, seed = 123) {

# set seed according to command argument `seed`

set.seed(seed)

# preallocate space to store estimators

msePrimeAvg <- 0.0

mseSamplAvg <- 0.0

# loop over simulation replicates

for (r in 1:reps) {

# simulate data according to command arguments `n` and `distr`

if (dist == "gaussian") {

x = rnorm(n)

} else if (dist == "t1") {

x = rcauchy(n)

} else if (dist == "t5") {

x = rt(n, 5)

} else {

stop(paste("unrecognized dist: ", dist))

}

# prime indexed mean estimator and classical sample average estimator

msePrimeAvg <- msePrimeAvg + estMeanPrimes(x)^2

mseSamplAvg <- mseSamplAvg + mean(x)^2

}

mseSamplAvg <- mseSamplAvg / reps

msePrimeAvg <- msePrimeAvg / reps

return(c(mseSamplAvg, msePrimeAvg))

}In order to indicate the option 2, we save the above codes in script [runSim.R].

54.4.1.1 Option 2

this example is only good for linux system

The [

runSim.R] script to include argumentsseed(random seed),n(sample size),dist(distribution) andrep(number of simulation replicates). Whendist="gaussian", generate data from standard normal; whendist="t1", generate data from t-distribution with degree of freedom 1 (same as Cauchy distribution); whendist="t5", generate data from t-distribution with degree of freedom 5. CallingrunSim.Rwill (1) set random seed according to argumentseed, (2) generate data according to argumentdist, (3) compute the primed-indexed average estimator and the classical sample average estimator for each simulation replicate, (4) report the average mean squared error (MSE)The [

autoSim.R] script to run simulations with combinations of sample sizesnVals = seq(100, 500, by=100)and distributionsdistTypes = c("gaussian", "t1", "t5").rep = 50is used for MSE.

cat resources/speed_up_in_r_programming/autoSim.R- Download the [

runSim.R] and [autoSim.R] scripts, and run the following codes, this will parallelly compute results from all combinations, and write output to appropriately named files.

Rscript resources/speed_up_in_r_programming/autoSim.R seed=280 rep=5054.4.1.2 Option 3

54.4.1.3 Serial code

We need to loop over 3 generative models (distTypes) and 20 samples sizes (nVals). That are 60 embarssingly parallel tasks.

This is the serial code that double-loop over combinations of distTypes and nVals:

## simulation study with combination of generative model `dist` and

## sample size `n` (serial code)

simres1 = matrix(0.0, nrow = 2 * length(nVals), ncol = length(distTypes))

i = 1 # entry index

system.time(

for (dist in distTypes) {

for (n in nVals) {

#print(paste("n=", n, " dist=", dist, " seed=", seed, " reps=", reps, sep=""))

simres1[i:(i + 1)] = compare_methods(dist, n, reps, seed)

i <- i + 2

}

}

)## user system elapsed

## 36.303 0.024 36.329## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 0.0103989436 0.017070603 312.4001

## [2,] 0.0410217819 0.066503177 200.3237

## [3,] 0.0065484669 0.011260420 173.9631

## [4,] 0.0297390639 0.047465397 199.5330

## [5,] 0.0056445593 0.007754855 68026.7023

## [6,] 0.0215380206 0.040039145 1230343.1341

## [7,] 0.0040803523 0.006871930 43609.7815

## [8,] 0.0165144049 0.032353077 931755.3182

## [9,] 0.0032566766 0.005417194 30283.1286

## [10,] 0.0161191554 0.026330133 684726.8788

## [11,] 0.0027565672 0.004444172 22306.1369

## [12,] 0.0145039253 0.022820075 539105.3392

## [13,] 0.0024915830 0.003798500 17119.0807

## [14,] 0.0122801335 0.022788299 435528.4778

## [15,] 0.0023706676 0.003360507 13531.4104

## [16,] 0.0112703627 0.016674640 111.4673

## [17,] 0.0020190283 0.003147367 10973.3489

## [18,] 0.0106157492 0.016027485 278.9663

## [19,] 0.0017567901 0.002863640 9069.6647

## [20,] 0.0096185720 0.016444671 261373.7646

## [21,] 0.0016441481 0.002637964 7629.9867

## [22,] 0.0081784426 0.013710539 296.6235

## [23,] 0.0015075246 0.002498450 6498.2362

## [24,] 0.0088018140 0.012909942 191986.6388

## [25,] 0.0014372130 0.002308089 5603.9395

## [26,] 0.0077292632 0.012789483 171280.5448

## [27,] 0.0012924543 0.002216936 4889.8739

## [28,] 0.0069012154 0.011052562 170.3975

## [29,] 0.0011994654 0.001987311 4299.6838

## [30,] 0.0067559611 0.011291788 178.7454

## [31,] 0.0011642413 0.001888637 3806.8472

## [32,] 0.0070131993 0.010048327 140.2389

## [33,] 0.0011566121 0.001873365 3401.9766

## [34,] 0.0065066558 0.009020973 34.1644

## [35,] 0.0010506067 0.001595430 3049.0432

## [36,] 0.0060026682 0.010338424 103578.0598

## [37,] 0.0009770234 0.001618095 2768.4517

## [38,] 0.0054705674 0.009229294 143.554454.4.1.4 Using mcmapply

Run the same task using mcmapply function (parallel analog of mapply) in the parallel package:

## simulation study with combination of generative model `dist` and

## sample size `n` (parallel code using mcmapply)

library(parallel)

system.time({

simres2 <- mcmapply(compare_methods,

rep(distTypes, each = length(nVals), times = 1),

rep(nVals, each = 1, times = length(distTypes)),

reps,

seed,

mc.cores = 4)

})## user system elapsed

## 27.444 0.607 19.805## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 0.0103989436 0.017070603 312.4001

## [2,] 0.0410217819 0.066503177 200.3237

## [3,] 0.0065484669 0.011260420 173.9631

## [4,] 0.0297390639 0.047465397 199.5330

## [5,] 0.0056445593 0.007754855 68026.7023

## [6,] 0.0215380206 0.040039145 1230343.1341

## [7,] 0.0040803523 0.006871930 43609.7815

## [8,] 0.0165144049 0.032353077 931755.3182

## [9,] 0.0032566766 0.005417194 30283.1286

## [10,] 0.0161191554 0.026330133 684726.8788

## [11,] 0.0027565672 0.004444172 22306.1369

## [12,] 0.0145039253 0.022820075 539105.3392

## [13,] 0.0024915830 0.003798500 17119.0807

## [14,] 0.0122801335 0.022788299 435528.4778

## [15,] 0.0023706676 0.003360507 13531.4104

## [16,] 0.0112703627 0.016674640 111.4673

## [17,] 0.0020190283 0.003147367 10973.3489

## [18,] 0.0106157492 0.016027485 278.9663

## [19,] 0.0017567901 0.002863640 9069.6647

## [20,] 0.0096185720 0.016444671 261373.7646

## [21,] 0.0016441481 0.002637964 7629.9867

## [22,] 0.0081784426 0.013710539 296.6235

## [23,] 0.0015075246 0.002498450 6498.2362

## [24,] 0.0088018140 0.012909942 191986.6388

## [25,] 0.0014372130 0.002308089 5603.9395

## [26,] 0.0077292632 0.012789483 171280.5448

## [27,] 0.0012924543 0.002216936 4889.8739

## [28,] 0.0069012154 0.011052562 170.3975

## [29,] 0.0011994654 0.001987311 4299.6838

## [30,] 0.0067559611 0.011291788 178.7454

## [31,] 0.0011642413 0.001888637 3806.8472

## [32,] 0.0070131993 0.010048327 140.2389

## [33,] 0.0011566121 0.001873365 3401.9766

## [34,] 0.0065066558 0.009020973 34.1644

## [35,] 0.0010506067 0.001595430 3049.0432

## [36,] 0.0060026682 0.010338424 103578.0598

## [37,] 0.0009770234 0.001618095 2768.4517

## [38,] 0.0054705674 0.009229294 143.5544We see roughly 3x-4x speedup with

mc.cores=4.mcmapply,mclapplyand related functions rely on the forking capability of POSIX operating systems (e.g. Linux, MacOS) and is not available in Windows.parLapply,parApply,parCapply,parRapply,clusterApply,clusterMap, and related functions create a cluster of workers based on either socket (default) or forking. Socket is available on all platforms: Linux, MacOS, and Windows.

54.4.1.5 Using clusterMap

The same simulation example using clusterMap function:

cl <- makeCluster(getOption("cl.cores", 4))

clusterExport(cl, c("isPrime", "estMeanPrimes", "compare_methods"))

system.time({

simres3 <- clusterMap(cl, compare_methods,

rep(distTypes, each = length(nVals), times = 1),

rep(nVals, each = 1, times = length(distTypes)),

reps,

seed,

.scheduling = "dynamic")

})## user system elapsed

## 0.025 0.008 16.310## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 0.0103989436 0.017070603 312.4001

## [2,] 0.0410217819 0.066503177 200.3237

## [3,] 0.0065484669 0.011260420 173.9631

## [4,] 0.0297390639 0.047465397 199.5330

## [5,] 0.0056445593 0.007754855 68026.7023

## [6,] 0.0215380206 0.040039145 1230343.1341

## [7,] 0.0040803523 0.006871930 43609.7815

## [8,] 0.0165144049 0.032353077 931755.3182

## [9,] 0.0032566766 0.005417194 30283.1286

## [10,] 0.0161191554 0.026330133 684726.8788

## [11,] 0.0027565672 0.004444172 22306.1369

## [12,] 0.0145039253 0.022820075 539105.3392

## [13,] 0.0024915830 0.003798500 17119.0807

## [14,] 0.0122801335 0.022788299 435528.4778

## [15,] 0.0023706676 0.003360507 13531.4104

## [16,] 0.0112703627 0.016674640 111.4673

## [17,] 0.0020190283 0.003147367 10973.3489

## [18,] 0.0106157492 0.016027485 278.9663

## [19,] 0.0017567901 0.002863640 9069.6647

## [20,] 0.0096185720 0.016444671 261373.7646

## [21,] 0.0016441481 0.002637964 7629.9867

## [22,] 0.0081784426 0.013710539 296.6235

## [23,] 0.0015075246 0.002498450 6498.2362

## [24,] 0.0088018140 0.012909942 191986.6388

## [25,] 0.0014372130 0.002308089 5603.9395

## [26,] 0.0077292632 0.012789483 171280.5448

## [27,] 0.0012924543 0.002216936 4889.8739

## [28,] 0.0069012154 0.011052562 170.3975

## [29,] 0.0011994654 0.001987311 4299.6838

## [30,] 0.0067559611 0.011291788 178.7454

## [31,] 0.0011642413 0.001888637 3806.8472

## [32,] 0.0070131993 0.010048327 140.2389

## [33,] 0.0011566121 0.001873365 3401.9766

## [34,] 0.0065066558 0.009020973 34.1644

## [35,] 0.0010506067 0.001595430 3049.0432

## [36,] 0.0060026682 0.010338424 103578.0598

## [37,] 0.0009770234 0.001618095 2768.4517

## [38,] 0.0054705674 0.009229294 143.5544Again we see roughly 3x-4x speedup by using 4 cores.

clusterExportcopies environment of master to slaves.

54.5 Package development

Learning resources:

Book _R Packages_ by Hadley Wickham

RStudio tutorial: https://support.rstudio.com/hc/en-us/articles/200486488-Developing-Packages-with-RStudio